An online community for Ateneans featured a story detailing a student’s experience with a Chinese national who gave her a bowl of bones and leftovers for dinner.

The story was submitted to “ADMU Freedom Wall,” a Facebook page where Atenean students can share their thoughts, opinions and stories supposedly concerning themselves or the school.

According to the post, the student was invited by her best friend, a Chinese Filipino, to study in his house and finish their project after school hours.

While his parents were “very kind and accommodating,” it was his relatives from mainland China whom she found “very racist.”

“Apparently, they have relatives from China who just moved to manage a new casino business. They are very racist. They gave me mean looks at first,” the student recounted.

During dinnertime, her best friend ate with his family while she waited for her own food via delivery.

One of her friend’s Chinese relatives approached her while she waited and then presented her with a bowl of bones and leftover scraps.

According to the student, the relative placed it on the floor, gestured for her to eat it and then said, “Dog food.”

Shocked beyond words, she walked out of the room and then decided to go home after.

“(My friend) says I’m overreacting with how I’m avoiding him and tells me he doesn’t like his mainland relatives din but they just tolerate their behavior,” the student said.

#ADMUFreedomWall35603My best friend invited me over to study at their place. He's from a Chi-Fil family and, and his…

Posted by ADMU Freedom Wall on Wednesday, July 24, 2019

Other Filipinos who read the post claimed that she should’ve fought back against the Chinese relative while there were those who suggested she “end” her friendship with the guy immediately.

There were also others who questioned the “casino business” of her friend’s family amid the rise of Chinese nationals engaging in online casinos or Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators.

It was not the first time that Chinese nationals had exhibited such behaviors or attitude to Filipinos.

Last year, a Twitter user shared that a Chinese national cut in line of a cashier in a retail store to pay for a shirt. One staff member called him out but he reportedly ignored the warning.

While the veracity of such accounts are difficult to verify as many are written anonymously, they are similar to many reports from around the world.

Why Chinese visitors are behaving badly

Millions of Chinese mainlanders touring the world have been on the uptick since the early 2000s alongside China’s staggering economic growth.

It would be the first time for many of them to board a plane, see the major capitals and encounter diverse ethnicities. More mature Chinese, in particular, came from a time of political turmoil which isolated them from the world. They did not know enough about destinations and cultures before encountering them.

More and more Chinese have been traveling since, spending inordinate amounts of money abroad. In 2015, average spending for every Chinese tourist was $7,200 per visit in the United States—that is roughly converted to P327,600.

For economies, the tourism trend—and the income from their consumption and shopping frenzy—would be welcome, but for locals who are sensitive about having their customs respected, it would take some adjustment. Stereotypes that Chinese tourists misbehave are then formed, fueling sentiments bordering on xenophobia.

Back in China, the government finds such reports of its rowdy nationals embarrassing. Since 2013, Chinese embassies have issued etiquette guides or handbooks to nationals visiting foreign lands. The tips are inadvertently revealing, among which are:

- Don’t pick noses in public.

- Don’t pee in pools.

- Don’t curse at locals.

- Don’t leave footprints on the toilet seat.

- Don’t steal airline life jackets.

- Don’t click fingers at Germans, since finger clicking is for dogs.

- Don’t cut in line.

While more “civilized” travelers would frown upon these, history shows that at particular points in history, every other ethnicity was once denounced as unruly, unworthy foreign visitors.

In the Philippines, the discussion is more than just about tourism

The number of visitors from China in the Philippines increased sharply from just over 155,000 in 2009, increasing by roughly 100,000 every year.

Data from the Bureau of Immigration shows, however, that the number of visitors doubled from 675,663 in 2016, around the start of the Duterte administration, to 1.255 million in 2018.

While tourism is usually a boon for the economy, for the average Filipino, however, it is tricky to remove national politics and geopolitics from the picture.

Latest surveys showed that Filipinos have “little trust” in China as the Duterte administration continues to pursue friendly relations with the Asian giant even over longstanding maritime disputes.

Polling firm Social Weather Stations last week reported that Filipinos’ trust rating with China went down compared to March when it was neutral. It was also the lowest trust rating recorded since June 2018.

Earlier this month, a property consulting firm revealed that Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators, collectively an online gambling industry dominated by Chinese workers based in the Philippines, would soon overtake the country’s information technology and business processing management sector in terms of office space demand.

The influx of Chinese workers is also driving the price of residential spaces up, making condominium units too expensive for the many Filipino buyers and tenants.

It was a testament of the Chinese’s steadily growing presence in the Philippines, particularly their hand in an industry that is reported to be overwhelming the Bureau of Internal Revenue’s capacity to issue tax identification numbers.

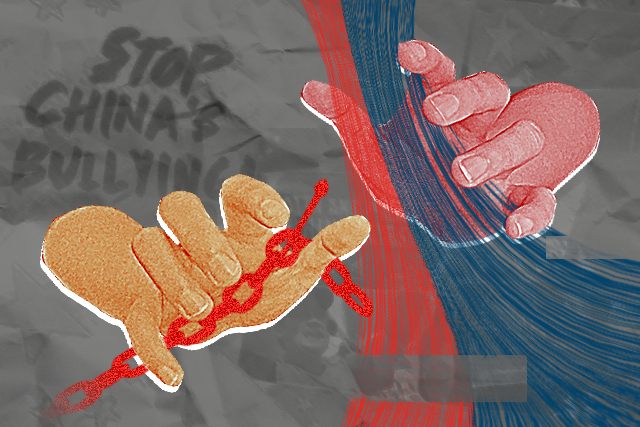

“They (the Chinese) are complaining because our system is not set up to register 100,000 (POGO-related businesses) a week then all of a sudden you have 100,000… It’s not our fault—they didn’t register!” Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III previously explained. — With Camille Diola; Artwork by Uela Altar-Badayos