Women researchers are less likely to comment on academic work, and it shows a subtle gender bias in academia. If women are less likely to comment, they could be excluded from or marginalized in important scholarly debates and networks.

In academic journals, comments or letters to the editor are short papers that respond to a previously published paper, usually to point out potential flaws or discrepancies or to comment on exceptional studies.

The practice of commenting on published work plays an essential role in promoting scholarly discussion, knowledge exchange and scientific advancement. Many leading general scientific research journals publish unsolicited comments.

Comments produce impact

Commenting generally takes place in leading journals so it is an ideal opportunity for high visibility career advancement. Comments are also early indicators of the future impact of commented papers as commented papers are much more cited than non-commented papers. In fact, papers with comments and responses are more likely to be the most cited papers of a journal. Hence, if men and women writing comments differentially target men and women’s research for commentary, this impacts the relative prominence of men and women in scholarly debate.

A few years ago, I published a comment letter with co-author Wilkes. Since then, I have been reading more comments published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). One pattern I noticed is that women seem to be less likely to comment on published work written by men.

To consider whether there are gender biases in commenting on published work, my co-authors and I conducted a study using author information from all comment letters published over 16 years in PNAS and Science, two of the world’s most comprehensive, high-impact and widely read scientific journals.

Over a period of several months, we collected and hand-coded the author information of 1,350 comment letters referring to 1,236 research articles. We searched authors profiles online to obtain images for our measure of the author’s gender; we note that images are an imperfect way to obtain gender.

Women less likely to comment

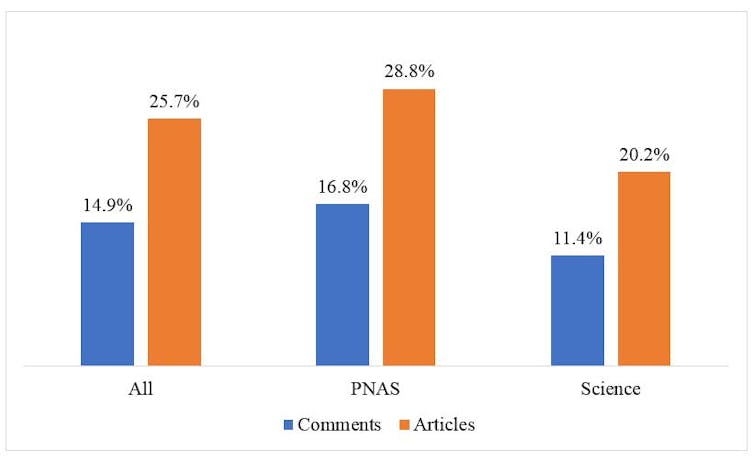

Women are still significantly under-represented in authoring research articles in leading journals — including both PNAS and Science. The under-representation of women in the authorship of comment letters could simply reflect the gender difference in publication, rather than reflecting women’s lower engagement in commenting per se.

If this is the case, we would also expect that the share of female-authored comments should be lowest in the physical sciences, where women are most strongly under-represented and higher in the social sciences where there are more women.

Our analysis shows, however, that the percentage of female-authored comments is significantly lower than the percentage of female-authored research articles. This suggests that women are indeed less likely to engage in academic commenting.

The pattern is consistent across the physical sciences, the biological sciences as well as the social sciences. It cannot be explained by variability in the field-specific gender ratio. Nor can pipeline effects explain the disparity — junior scholars are actually more likely to comment than others, and the gender imbalance remains when looking within the ranks of more and less senior scholars.

Women less likely to comment on men’s work

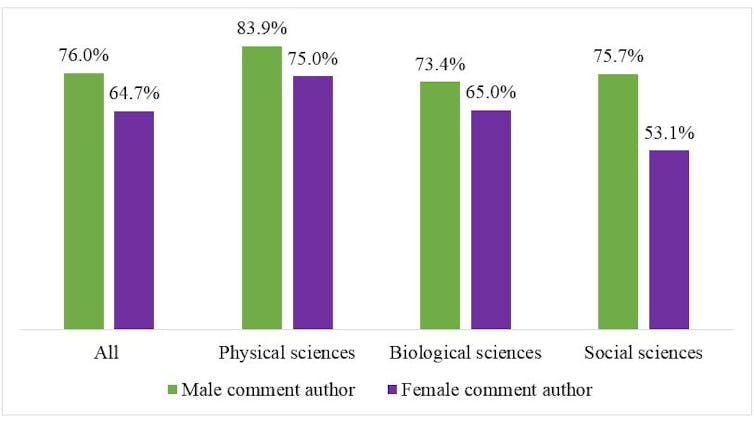

Our further analysis shows that both men and women are more likely to comment on men’s research. This is not surprising given men’s higher authorship rates in both PNAS and Science. However, women are relatively less likely to target articles authored by men.

Surprisingly, this pattern that women direct a lower share of their comments towards men’s research than do men is particularly pronounced in the social sciences, where women’s representation is higher.

Ultimately, in academic commenting two empirical patterns are clear. First, women are less likely than men to comment on published academic research. This disparity is greater than gender differences in the publication of research articles.

Second, there is also a gendered pattern in commenting: women comment writers are relatively less likely to engage with men’s research.

Author provided

Risky comments

A plausible explanation we put forward for why women are less likely to comment on men’s work is that the consequences of commenting are gendered. Publicly criticizing someone’s work can be a potentially high-risk form of scholarly contribution and engagement. Potentially, it can damage to one’s own reputation if one’s critique is perceived as invalid or unfair. It can also lead to retaliation in either the short or long term.

Women are considered less likeable when they are perceived as behaving assertively, and demonstrate success in male-dominated arenas. Hence, commenting in general could be disproportionately risky for women; this is particularly pronounced when the target is a male scholar insofar as it challenges the presumptive superiority of men.

Regardless of the mechanisms driving these empirical patterns, their impact is not trivial.

Women’s lower rates of commenting mean they benefit less from participation in high-impact scholarly debate.

The pattern that men comment on men’s research more while women comment on women’s more could impede scholarly exchange between men and women and further marginalize women within the scientific community.

Editorial attention to the issue of gendered patterns is essential to address gender bias in commenting more broadly. Editors are encouraged to specifically invite women to write comments, and especially to write comments on men’s published work. To protect women from the potential negative consequences of commenting, editors can serve a bridge in promoting friendly exchange between women authors and their target men authors.

Insofar as commenting also increases the visibility of commented-upon research, this would also help counter barriers to women’s representation in high-impact scholarly debates.![]()

Cary Wu, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, York University, Canada; Rima Wilkes, Professor of Sociology, University of British Columbia, and Sylvia Fuller, Professor, Sociology, University of British Columbia. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.