OAKLAND— A global race is on to develop smartphone apps and other types of mobile phone surveillance systems to track and contain the spread of the novel coronavirus.

The process known as “contact tracing,” which is used to control the spread of infectious diseases, was boosted last week when the top two smartphone software makers, Alphabet Inc’s Google and Apple Inc, said they were collaborating on apps that can identify people who have crossed paths with a contagious patient and alert them.

How can mobile phones help combat the new coronavirus?

Smartphones and some less-sophisticated mobile phones keep track of their location via cell-tower signals, Wi-Fi signals and the satellite-based global positioning system, known as GPS. Smartphones also use so-called Bluetooth technology to connect with nearby devices.

The location data can be used to monitor whether people, either individually or in aggregate, are obeying orders to stay inside their homes. It can also be used for contact tracing: determining whether people have been in contact with others who have the virus, so they can get tested or quarantined.

Smartphones can also be used to take surveys of people about their health via messaging, record their health histories via various forms of data entry and even produce a health “score” based on a combination of location information and health data.

How can phones help with contact tracing?

Using Bluetooth, smartphones can log other phones they have been near. If someone becomes infected, there is a ready list of their prior encounters. Phones on the list would get push notifications urging them to get tested or self-isolate.

In principle, this system is more efficient than traditional contact tracing methods that require large staffs to interview patients about their travels and then call or knock on the doors of contacts.

The Bluetooth solution is far from perfect. Phones can log one another even when 15 feet apart or on separate sides of a wall, even though a cough from an infected person likely would not be problematic in those cases. But developers have been working on ways to better define “contacts” based on the length and strength of so-called handshakes between devices.

Bluetooth also remains more accurate than GPS or cell tower location data, which can wrongly associate everyone on a busy city block as contacts.

Are any of these methods currently in use?

Singapore pioneered contact tracing via Bluetooth with an app called “TraceTogether.” Israel, which made headlines by employing its powerful government surveillance system to track cases, has also rolled out an app called The Shield. India also has an app.

South Korea is using mobile phone location data for contact tracing, while Taiwan uses it for quarantine enforcement and is also developing an app. China is employing a range of app-based tracking systems.

Meanwhile, dozens of efforts to develop contact tracing apps are underway around the world, many led by government research institutes and health authorities. In Europe, for example, a German-led effort is aiming to rally other European countries behind a technology platform that could support contact tracing apps across the 27-member EU. But several other European countries are pursuing their own apps. An effort is also underway in the United Kingdom.

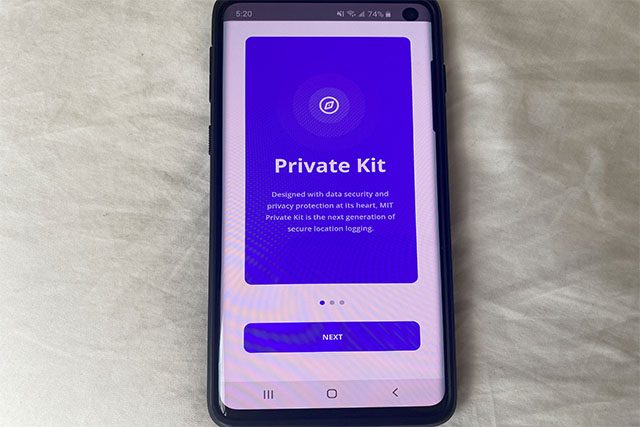

The United States government has yet to promote an app, but at least two university research groups and one ad-hoc software development team are trying to gain endorsements from state and local bodies.

How do Apple and Google fit it?

The two companies said they were concerned about competing approaches and agreed to develop tools, to be released in May, that will enable apps to “handshake” with one other. They also address battery drain and other issues that have limited the utility of some early apps.

Apple and Google also plan to go a step further later this year by integrating logging functionality directly into their phone software nearly worldwide.

People who catch the virus would still need to download an app to initiate contact notifications, but even those without apps could receive notifications.

Are there privacy and security concerns?

Yes. The most sensitive issue is who can view a phone’s list of devices it has crossed. Nearly everyone agrees on deleting logs after about one month.

The tools coming from Google and Apple keep names off contact lists and leave the lists secret to everyone involved, which has drawn plaudits from privacy experts. Only governments, which must verify that people who say they tested positive for coronavirus actually did so, would know the identity of disease carriers, and even they would not have access to the contact lists.

But some governments and technologists favor collecting a central database of all “handshakes” between phones because it is an easier system to design and manage. Privacy advocates worry that such a database would be a hackers’ goldmine and prone to governmental abuse.

Some researchers have suggested apps also track GPS information to better map the spread of the coronavirus. But GPS data could undermine people’s privacy and leave places visited by people who test positive ostracized, activists said.

Will people be required to turn on contact tracing?

No country is known to have required an app, but workplaces or other facilities could end up mandating usage. Apple and Google said that apps seeking to use its tools would need to be voluntary.

But the apps won’t achieve their purpose unless they are widely used. Some epidemiologists have said at least 60% of a country needs to activate digital contact tracing for it make an impact. —Reporting by Paresh Dave; Additional reporting by Stephen Nellis, Raphael Satter and Douglas Busvine; Editing by Jonathan Weber and Grant McCool