China is shaping the future of economic development through its Belt and Road Initiative, an ambitious multi-billion-dollar international push to better connect itself to the rest of the world through trade and infrastructure. Through this venture, China is providing over 100 countries with funding they have long sought for roads, railways, power plants, ports and other infrastructure projects.

This mammoth effort could generate broad economic growth for the countries involved and the global economy. The World Bank estimates that recipient countries’ gross domestic product could rise by up to 3.4% thanks to Belt and Road financing.

But development often expands human movement and economic activity into new areas, which can promote deforestation, illegal wildlife trafficking and the spread of invasive species. Past initiatives have also sparked conflict by infringing on Indigenous lands. These projects were often approved without the recognition or consent of local Indigenous communities.

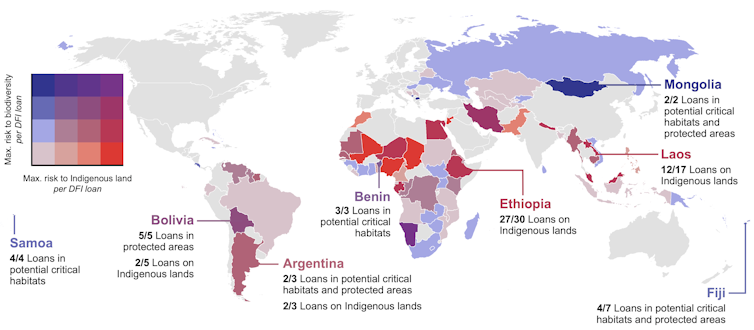

In a newly published study, our team of development economists and conservation scientists mapped the risks Chinese overseas development finance projects pose for Indigenous lands, threatened species, protected areas and potential critical habitats for global biodiversity conservation. We found that more than 60% of China’s development projects present some risk to wildlife or Indigenous communities.

Diverse projects and risks

Our study examines 594 development projects financed by the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China. We created a database to track the characteristics and locations of projects that these two “policy banks” supported between 2008 and 2019. During this period, the banks committed more than US$462 billion in development finance to 93 countries – roughly as much as the World Bank, the traditional global leader in development finance, committed in that time.

Nearly half of all projects financed by these two banks are located within potential critical habitats. These are areas that might be essential for conservation and require special protection considerations, according to the International Finance Corporation, a unit of the World Bank that promotes private investment in developing countries.

One in three of the projects fall within existing protected areas, and nearly one in four overlaps with lands owned or managed by Indigenous peoples. In total, we calculate that China’s development finance portfolio could impact up to 24% of the world’s threatened amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles.

Adapted from Yang, et al., 2021

The greatest risks lie in South America, Central Africa and Southeast Asia. All of the projects that China’s policy banks are financing in Benin, Bolivia and Mongolia overlap with existing protected areas or potential critical habitats. More than 65% of Chinese development projects in Ethiopia, Laos and Argentina are located within Indigenous lands.

On average, risks to Indigenous lands are greatest from extraction and transportation projects, such as mines, pipelines and roads. The greatest threats to nature are energy projects, including dams and coal-fired power plants. For example, a cascade of seven hydropower dams along the the Nam Ou River in Laos has displaced Indigenous communities that depended on local ecosystems for their livelihoods.

How the World Bank addresses these risks

China may be the world’s largest country-to-country development lender, but it’s not the only funding source for emerging economies. The World Bank, an international organization funded mostly by wealthy nations, has been a leading source of development finance over the last 40 years – but its approach is markedly different from China’s.

In the 20th century, critics assailed the World Bank for funding projects that caused environmental damage and social conflict. But in the past 30 years it has enacted a series of environmental and social reforms that are designed to steer lending toward more inclusive and sustainable development projects. Just this year, the bank committed to aligning its lending with the Paris Agreement on climate change by 2023.

China’s rapid economic growth since the 1980s has made it one of the world’s top polluters. Now its leaders are working to improve their country’s environmental performance.

China has created a national system of protected areas and has pledged to make its domestic economy carbon-neutral by 2060. But it has made no such reforms in its foreign lending.

Comparing projects financed by the World Bank from 2008-2019 with our list of Chinese loans, we found that on average China’s projects pose significantly greater risk to nature and Indigenous lands, primarily in the energy sector.

The World Bank also has a concerning proportion of loans in high-risk areas. Notably, the roads, railways and other transportation projects that it financed during this period pose risks to biodiversity that are nearly equivalent to those posed by similar projects financed by China.

For example, in 2016 the World Bank financed a major road project across the Democratic Republic of the Congo, including Indigenous peoples’ territory, opening them up to the loss of property and livelihoods, as well as violence. A formal internal investigation found that “serious harm” had occurred and directed the World Bank to manage future projects more carefully.

Making development finance sustainable

China has an opportunity with the Belt and Road Initiative to improve infrastructure networks around the world in a way that is both sustainable and inclusive. Recently it published the inter-ministerial “Green Development Guidelines for Overseas Investment and Cooperation,” a set of voluntary guidelines produced by Chinese experts from universities, governmental and non-government organizations and international experts, including two of us (Kevin Gallagher and Rebecca Ray). This report urges Chinese investors to respect host country environmental standards. When those standards are lower than China’s, the guidelines recommend using international environmental standards.

In a promising step, President Xi Jinping announced on Sept. 21, 2021 at the U.N. that China would not build new coal-fired power plants abroad. Just as importantly, he announced that China will “step up support for other developing countries in developing green and low-carbon energy.”

Such a powerful shift can open renewable energy access across the developing world. However, our study shows that investments in low-impact sectors can still carry risks to vulnerable ecosystems and communities. We believe these climate commitments should be complemented with similar social and environmental performance standards that take into account local risks to biodiversity and Indigenous peoples.

[Over 110,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Currently China is preparing to host the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity – the main global agreement that commits nations to protect species and ecosystems around the world. Sessions will take place online in October 2021 and in person in Kunming in the first half of 2022. This event is a unique opportunity for China to address social and environmental risks from its global development activities.

We believe that China would be wise to adopt new recommendations set forth by its Ministry of Ecology and Environment, in collaboration with international experts, including two of us (Kevin Gallagher and Rebecca Ray), that would require compulsory environmental management systems for projects supported by public Chinese banks to prevent and mitigate risks. This would raise the bar for Western lenders, who also need to improve their standards but fear losing business to Chinese lenders.

By minimizing harmful impacts from the projects it funds, we believe China could make the Belt and Road Initiative a win-win for itself, host countries and the global economy.

This article has been updated to include President Xi Jinping’s Sept. 21 announcement that China will stop building coal-fired power plants abroad.

Hongbo Yang, a former Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center, was joint lead author of the study described in this article.![]()

Blake Alexander Simmons, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Boston University; Kevin P. Gallagher, Professor of Global Development Policy and Director, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University, and Rebecca Ray, Senior Academic Researcher in Global Development Policy, Boston University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.