MANILA – Philippine construction firm Teravera Corp is planning to raise a fourth dollar loan in a year, after borrowing around $2.5 million to buy dozens of excavators, road rollers and dump trucks from China, South Korea and Japan.

Teravera is one of hundreds of local builders contributing to a surge in capital goods imports that has turned the country’s current account surplus into a deficit and knocked the Philippine peso down to 11-year lows against the dollar last month.

While the peso’s dip is raising eyebrows in a region where the the Thai baht and the Malaysian ringgit are flirting with multi-year highs, it’s come mainly because the Philippines, one of the world’s fastest growing economies, has been enjoying a construction boom.

Besides private construction, companies like Teravera are confident of more contracts coming from the government’s drive to upgrade its dilapidated roads, railways, ports and airports, which have been a drag on the economy.

“We have seen the government’s list of projects and they are bidding them out early, that is why we have been procuring equipment,” said Teravera vice-president Aldrin Cabrera.

He said the company is confident of getting subcontracted to build a long-delayed four-lane toll road project on the southern part of Luzon island later this year, as it is one of bigger players in the area.

Foreign and local businesses have been frustrated with former President Benigno Aquino’s Public Private Partnership (PPP) projects, which often took a long time to kick off because of red tape.

Game change: all projects govt-funded

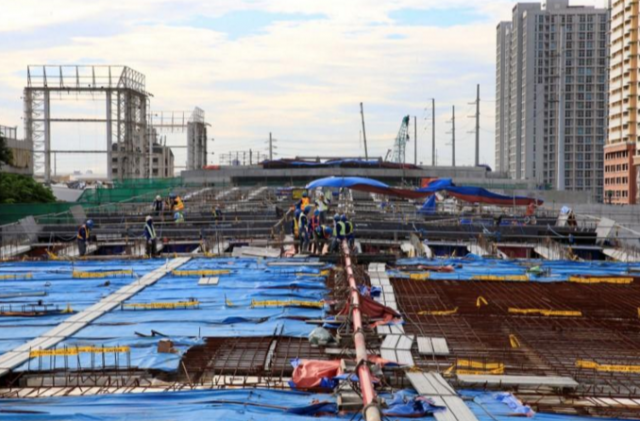

The game changer is that President Rodrigo Duterte, who took office just over a year ago, has decided that all projects will be entirely funded by the government, which his economic managers say should simplify the process. The controversial leader says he plans a $180 billion “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure campaign in his six-year term.

Duterte has already approved the auction of 21 projects worth $16 billion, including the overhaul of Manila’s shabby airport and a railway line on Mindanao island in the south. Other projects include upgrading ports, roads, rail links and irrigation.

Despite security problems linked to the spread of Islamic State militancy on Mindanao and Duterte’s bloody war on drugs, investors have welcomed the commitments, but say they need to see progress on the ground.

“We see a high degree of commitment and seriousness in the executive branch and probability of sufficient financing…not for every project to be completed on schedule but for very substantial and significant progress,” said John Forbes, senior adviser at the American Chamber of Commerce in the Philippines.

“However, the capacity of the bureaucracy to process a huge volume of projects …(is) untested,” he added. “The Philippines is not China, where bulldozers rumble through neighborhoods at the government’s command.”

Worst-performing currency

To meet existing and anticipated pick-up in demand, imports of capital goods, mainly infrastructure-related, have risen more than 7 percent in the first five months of the year from the same period of 2016 to $12.1 billion. For the first time in 15 years, the Philippines is expecting its 2017 current account balance to be in a deficit of $600 million.

The peso is Asia’s worst performing currency this year, hitting lows close to 51 per dollar last month. At the market close in Manila on Friday, the peso traded 50.16 to the dollar, down 0.9 percent in 2017.

Policymakers are often reminded of the Asian financial crisis 20 years ago whenever external balances weaken, and most economies in the region have built solid surpluses to avoid a similar episode.

In the Philippines, Duterte’s administration dismisses such warnings.

“We are importing equipment because we are a developing country trying to make up for past neglect on infrastructure,” Budget Secretary Benjamin Diokno said last month.

Central bank deputy governor Diwa Guinigundo says the weak peso boosts the purchasing power of Filipinos receiving $2 billion a month in remittances and, longer-term, will improve export demand.

Foreign investors, however, are more cautious.

“Until investors feel the imports work through the economy and push it to a higher growth path, the market’s focus would be on a deterioration in the balance of trade,” said Joey Cuyegkeng, senior economist at ING.

“We expect gradual (peso) weakening.”

Near term, around $40 billion in yearly inflows from outsourcing contracts and from millions of citizens working overseas mean the trade gap is covered. But Cuyegkeng says in two years time those inflows would barely cover the gap.

Duterte has promised to usher in a “golden age of infrastructure” by raising annual spending to 7 percent of GDP from less than 3 percent previously and above the 5 percent average of neighboring countries.

Encouraged by better budget planning and a crackdown on red tape, Nomura’s economists estimate 90 percent of the money lined up for infrastructure would be spent. On the ground, builders share the view.

“Some of the projects may sound ambitious, but they are needed. They will happen and it is just a question of time,” said Edgar Saavedra, president and chief operating officer of building company Megawide Construction Corp.