Pandemics change everything, including the way we design buildings.

After the 1918 Spanish flu and the scourge of tuberculosis, there was a push for “healthier” buildings, “full of light and air,” as the Swiss architect Le Corbusier put it. This translated into the clean lines and white surfaces of what came to be known as the “International Style” of architecture. The hygienic qualities of these modernist buildings were generally more aesthetic than real, but designs such as Alvar Aalto’s competition-winning Paimio sanatorium did provide the abundance of light and air recommended by Le Corbusier.

The COVID-19 crisis is likely to change building design again. Its health effects have not only been physical but also psychological. Our early ancestors evolved mostly outside in constantly changing natural environments. Yet the indoor spaces where we now spend much of our lives separate us from that world. One of the lessons of the current lockdowns is that we may need to change that.

Nature’s calming effects

Walks in the park, hikes in the forest and strolls along the beach are known to relieve stress. Spending time in nature also improves our ability to focus, and there’s even evidence that it helps us to heal physically as well.

For most of us, the recent lockdowns have led to an unprecedented shrinking of our worlds. Even under normal circumstances, however, our ability to spend time outdoors is often limited by work, family responsibilities or a simple lack of mobility. People in the United States, for example, already spent almost 90% of their time indoors long before the current crisis.

Interior plants can help, as can pets. But neither of these seems to have quite the same restorative effects as contact with wild nature, which alone has the capacity to evoke the sublime, a sense of being in the presence of something much larger than ourselves.

Wherever you happen to live, though, the Earth’s largest wilderness, its atmosphere, is only the thickness of a pane of glass away. And although buildings are typically designed to keep the weather out, there are powerful reasons to welcome its movement into our homes – the most important being that it seems to have a unique capacity to calm us.

Moving light patterns reflected from a wind-disturbed water surface, of the kind we typically see under boats and bridges, for example, have been shown to have a significant calming effect on heart rate, and can also help to keep us alert.

More recent work has suggested that this kind of familiar natural movement makes us feel connected to the present moment, in a way that mimics meditative practices such as mindfulness, but without requiring our active attention.

As someone who teaches and writes about architecture, I’ve spent the last two decades looking at how nature can be more effectively brought into our buildings, beyond just buying fish tanks and potted plants.

A number of buildings already successfully bring the movements of the weather indoors. I first encountered these in Japan, where designers such as Kengo Kuma and Toshihito Yokouchi have produced stunning indoor environments animated by the natural movements of the sun, wind and rain.

‘Let the sun come in, let the wind come in’

Designing all buildings this way would clearly take a great deal of money and time. But there are simple ways that you can create such effects in your own home right now, and at minimal cost. All of the following examples were created for less than US$50 using existing residential windows and balconies.

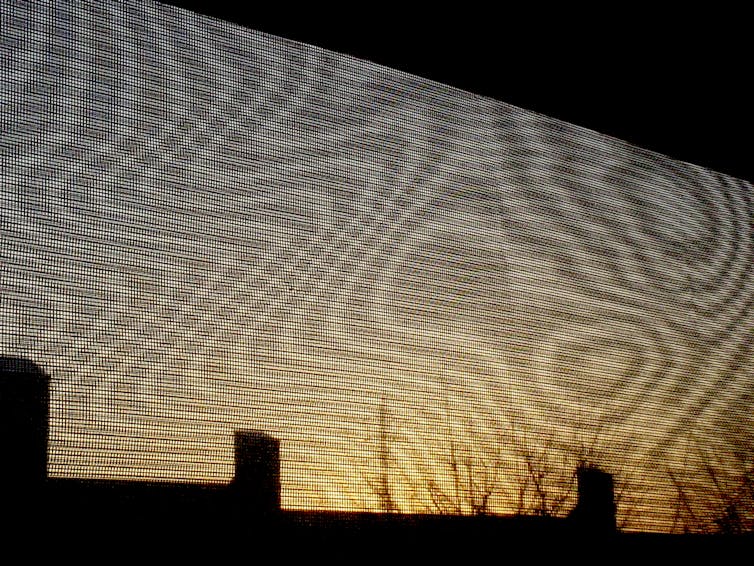

Placing an insect screen and a net curtain outside a window, for example, will generate moiré patterns that change as the wind varies. This works even on overcast days, but in direct sun the moiré patterns are also cast as moving shadows on interior surfaces.

If you have a deck or balcony that receives direct sunlight, the wind-generated movements of foliage can be projected onto a translucent shade or blind to make them seem part of the interior.

If the foliage is far enough away, wind-animated images of the sun can also be cast on indoor surfaces.

You can also project wind-animated reflected sunlight onto indoor surfaces by placing a shallow tray of water on a sun-facing balcony. This effect can even be recreated at night by directing an external security light onto the water surface. The same setup can also project ripples caused by rain.

Rather than thinking of the weather as an adversary that we need to shield ourselves from, then, it might be better to consider it a friend and welcome it back into our homes – particularly if we’re going to be spending a lot more more time there in the future.

On the subject of mistaking the weather as a foe, the late-20th century Indian mystic Osho used the following metaphor to describe the folly of trying to protect ourselves from all of life’s uncertainties:

“Existence is trying from everywhere to reach you, but you are closed. Not a single window is open. You have filled even small cracks in the wall out of fear, for the sake of security. This is not security, this is suicide. Open all the doors, all the windows. Let the sun come in, let the wind come in, let the rain come in.”

We might do well, it seems, to also heed Osho’s advice in the design of our homes

![]()

Kevin Nute, Assistant Professor of Architecture, University of Hawaii. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.