A humanitarian aid organization stressed the need to give importance to children’s vaccination following reports that the country has one of the highest numbers of “zero-dose” kids globally.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) on Tuesday said that the Philippines has one million “zero-dose” children or those who did not receive any routine vaccine in their childhood.

According to UNICEF, these are vaccines that protect the kids from the following diseases:

- Tuberculosis

- Hepatitis B

- Diphtheria

- Pertussis

- Tetanus

- Haemophilus influenzae Type B

- Poliovirus

- Pneumonia and meningitis

- Measles, mumps, and rubella

They are given during a child’s youngest years— from birth until they reach one year old.

The United Nations agency said that 67 million children worldwide missed their routine vaccination between 2019 and 2021, according to its 2023 State of World’s Children Report.

RELATED: People lost faith in childhood vaccines during COVID pandemic, UNICEF says

Of these, 48 million were considered “zero-dose” children or those who failed to receive a single routine vaccination in their early years.

Philippines’ ranking

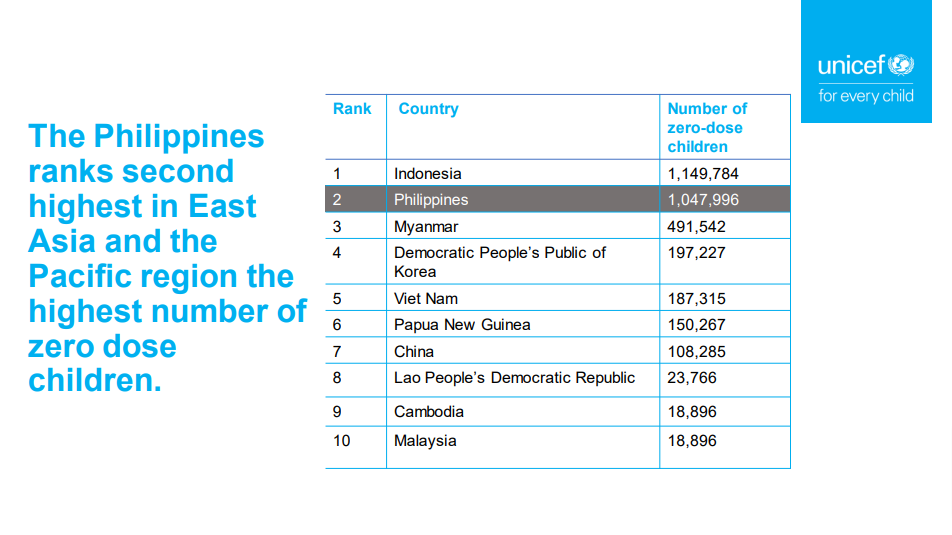

The Philippines has one million of them, placing the country with the second-highest number of zero-dose children in East Asia and the Pacific Region.

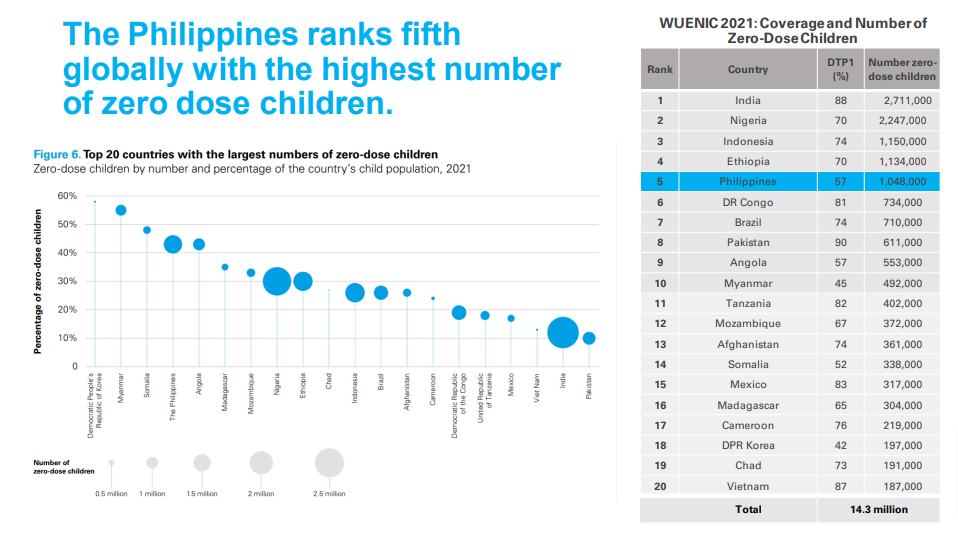

The country also ranks fifth with the highest number of zero-dose children globally.

UNICEF immunization specialist Carla Orozca said that the zero-dose figures for the Philippines, India, Indonesia and Myanmar were especially notable.

The Philippines likewise recorded one of the steepest declines in the perception of the importance of childhood vaccines before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, registering at -24.5% points.

Kathleen Solis, an expert in social and behavior change communication, said that the case of these unvaccinated children is a “story of inequity.”

She added that the situation calls for urgent collective action from the government, the parents and/or the children’s guardians.

UNICEF executive director Catherine Russell also had similar comments.

“At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists rapidly developed COVID-19 vaccines that saved countless lives. But despite this historic achievement, fear, and disinformation about all types of vaccines circulated as widely as the virus itself,” she said.

“This data is a worrying warning signal. We cannot allow confidence in routine immunizations to become another victim of the pandemic. Otherwise, the next wave of deaths could be of more children with measles, diphtheria, or other preventable diseases,” Russell added.

Factors contributing to the low kids’ immunization rate were globally attributed to uncertainty about the response to the pandemic, growing access to misleading information, declining trust in expertise, and political polarization.

In the Philippines, UNICEF said these could be attributed to cultural concerns and concerns about vaccine safety, especially after the 2017 Dengvaxia controversy.

It added that the “precipitous fall in confidence” was seen among the public following unproven claims that the anti-dengue vaccine supposedly caused the deaths of those inoculated with it.

‘Child survival crisis’

The need to reduce the country’s massive figure of zero-dose children comes as the world suffers its largest sustained backslide of kid immunization in 30 years due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

UNICEF said that the failure to immunize children at their most vulnerable years would lead to a “child survival crisis.”

Such consequences include early death, exposure to infectious diseases due to climate change risk, and children being unable to reach their full potential.

The UN agency said that over 60,000 kids die annually before they reach five years old due to complications of premature birth, intrapartum complications, and infectious disease.

It also reported that the Southeast Asian country ranks 31st in over 120 countries assessed for children’s risk to climate change, which it said will affect their access to public health services.

“Overlapping climate crises will put further strain on children’s access to essential services, including clean water and primary health care,” UNICEF said. If these cannot be accessed in cases of severe weather as an effect of the climate crisis, the child will be at risk of being exposed to potentially infectious diseases in the area.

Moreover, children will “not reach their full potential” if they fail to receive routine vaccinations in their youngest — and most crucial — years.

“Vaccine-preventable diseases affect children’s physical and cognitive development and prevent them from becoming healthy, productive citizens,” the organization said.

It added that diseases are now reappearing in countries where they had previously been controlled due to the low confidence in vaccines.

In the case of the Philippines, polio, a vaccine-preventable disease, emerged on its shores 19 years after it was eradicated. It had an outbreak from 2019 to 2021.

RELATED: Philippines risks polio problem as parents skip child vaccines — WHO

Polio’s resurgence came after measles and dengue outbreaks hit the country in early 2019.

“We’re also seeing surges of cases in nations that hadn’t yet eliminated the diseases. Those include cholera, measles, and polio outbreaks,” UNICEF said in its report.

Russell cited routine immunizations, along with strong health systems, as the “best shot at preventing future pandemics, unnecessary deaths, and suffering.”

“With resources still available from the COVID-19 vaccination drive, now is the time to redirect those funds to strengthen immunization services and invest in sustainable systems for every child,” she added.

ALSO READ: Confidence in childhood vaccines fell by 25% in Philippines during pandemic — UNICEF