LONDON— The World Health Organization (WHO) is in the spotlight as it champions the global fight against the new coronavirus but faces a funding freeze from U.S. President Donald Trump’s government.

Here are main features of the WHO and its work:

What is it?

The WHO is an agency of the United Nations set up in 1948 to improve health globally. It has more than 7,000 people working in 150 country offices, six regional offices and its Geneva headquarters.

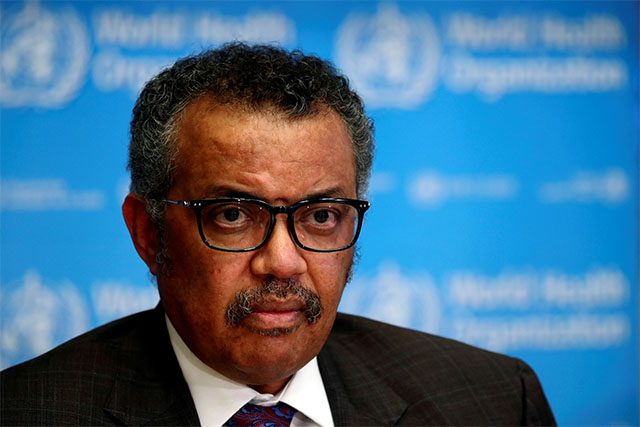

Its director general – currently the Ethiopian Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus – is elected for a five-year term. Tedros’ five-year term began on July 1, 2017.

What does it do?

The WHO’s stated aim is “to promote health, keep the world safe and serve the vulnerable”.

It has no power to impose health policies on national governments, but acts as an adviser and offers guidance on best practice in disease prevention and health improvement.

It has three main strands of work:

– aiming for universal health coverage in every country

– preventing and responding to acute emergencies

– promoting health and wellbeing for all

* What doesn’t it do?

Like a lot of international institutions, the WHO suffers from false perceptions about its scope and resources.

The WHO is not “the world’s doctor”: it does not provide treatment or conduct disease surveillance – although it does advise national and international authorities on those matters.

It has no powers of sanction, and the information it collates and publishes is only as good as the data and expertise it gets from member states and its technical specialists.

Is every country part of it?

The WHO has 194 member states: every country except Liechtenstein which is a member of the United Nations but not of its global health agency. They appoint representatives to The World Health Assembly, which convenes annually and sets WHO policies. These policies are implemented by the WHO’s Executive Board, composed of members technically qualified in health.

Who pays for it?

The WHO’s member states provide funding via two routes: assessed contributions and voluntary contributions. The WHO’s budgets are biennial, spanning two years. Its 2020-2021 budget is almost $4.85 billion, up 9% from the previous two-year period.

Assessed contributions are calculated on the basis of a country’s wealth and population, while voluntary contributions are often targeted by the donor at specific regions or diseases – such as polio, malaria, or infant mortality in poor areas.

Philanthropic foundations and multinational groups such as the European Commission are also major donors to the WHO.

The United States is the biggest overall donor and had contributed more than $800 million by the end of 2019 for the 2018-2019 biennial funding period. The Gates Foundation is the second largest donor, followed by Britain.

What are seen as its major successes and failures?

The WHO is widely credited with leading a 10-year campaign to eradicate smallpox in the 1970s and has also led global efforts to end polio, a battle that is in its final stages.

In the past few years, the WHO has also coordinated battles against viral epidemics of Ebola in Congo and Zika in Brazil.

In the current COVID-19 disease outbreak, while many have praised the WHO’s leadership, Trump has accused it of being China-centric and giving bad advice about the emerging pandemic.

This week, Trump said the WHO had “failed in its basic duty” and announced a temporary halt to U.S. funding – a move that prompted condemnation from many world leaders.

In the past, the WHO was accused of overreacting to the 2009-10 H1N1 flu pandemic and also faced widespread criticism for not reacting quickly enough to the vast Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014 that killed more than 11,000 people. —Reporting by Kate Kelland; Editing by Andrew Cawthorne