Despite significant steps forward in reforms, such as the K-to-12 basic education program and continuously increasing budgetary support, the quality of public education remains laggard in the country, as manifested by rising youth unemployment and poor achievement test scores of students from various levels.

This was the assessment of the advocacy group Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) regarding the state of Philippine education during a press briefing on Wednesday, July 5.

Businesses find it hard to match jobs with qualified talent. While education is supposed to increase the chances for a better life, this has not been the case for the two million unemployed Filipinos who have at least a high school diploma, a quarter of whom also have college diplomas.

PBEd chairperson Ramon Del Rosario said that, while the efforts of the Duterte administration on education was laudable, current reforms have still focused more on access rather than quality.

“Too much emphasis on access detached from quality has led to our children not learning enough and to our graduates not earning,” he said.

“Learning outcomes are tied to economic prospects, both at the individual and societal levels. Thus, we must do all that we can to ensure that our children and that our graduates are employed, especially given that the job market is robust yet remains thirsty for talent,” he added.

Indicators of quality education

PBEd executive director Love Basillote cited education and labor data highlighting the indications of the level of quality education that Filipinos are getting.

The average National Achievement Test (NAT) scores among elementary and high schools from 2010 to 2014 were still far behind the 2016 target set under the previous Philippine Development Plan (PDP).

Graduates taking licensure exams across all disciplines also performed significantly lower than the 53 percent 2016 PDP target, based on the data from the Commission on Higher Education (CHED).

“Filipino kids are falling behind,” Basillote said. “They are not learning.”

Problems in school-to-work transition

But the problem did not stop with educational institutions, as more issues present themselves when young Filipino graduates seek jobs.

About half of the 2.4 million unemployed Filipinos are from the 15 to 24 age group, according to the April 2017 Labor Force Survey of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

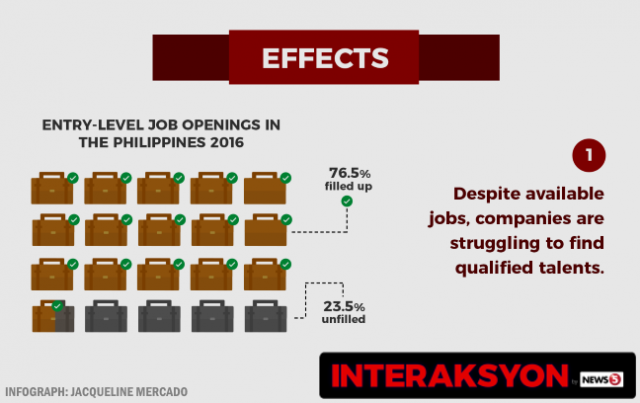

This is despite a PBEd study in 2016 that showed nearly a quarter of entry-level job openings remained unfilled.

Basillote said businesses found it difficult to match jobs with qualified talents.

“While education was supposed to increase the chances for a better life, this has not been the case for the two million unemployed Filipinos who have at least a high school diploma, a quarter of whom also have college diplomas,” she said.

It would also take at least a year for college graduates and three years for high school graduates to land their first full-time job, based on a study cited by the Asian Development Bank.

Government’s current reforms

When asked to rate the Duterte administration on education, Basillote gave a score of six out of 10, “as more work needs to be done in the education sector.”

She said the government should set a clear vision of where it wants to take education.

“For the first year, it’s great to continue K-to-12. But now is the point to say, what’s next? What are the quality investments that need to happen in order for education to support the type of economic growth that the administration is actually aspiring for?” she said.

Meanwhile, PBEd president Chito Salazar also raised concerns about the quality of education in colleges that would provide free tuition fee under the proposed free higher education act.

“We agree that there’s a need for higher education but it should be provided equitably to all,” he said.

“There should be this element of quality, meaning you don’t want to give them a low quality system. You want to get them access to good schools and to good programs,” he added.

As for the employability of K-to-12 graduates, Salazar acknowledged that some businesses may still be hesitant to hire them.

On the other hand, Del Rosario assured that some companies have started to come up with standards for hiring K-to-12 graduates, while efforts are underway to sell the idea of employing them.

So, what needs to be done in order to improve the quality of education in the country?

PBEd proposes the following measures:

1. Decentralizing the education system

According to Basillote, a decentralized system of education will ensure more effective service delivery.

She said there is a tendency for resources to go to waste under a highly centralized education system, citing cases where some government funds went to schools that did not need them.

2. Improve certification and training of teachers

Basillote said the poor content knowledge of teachers could be attributed to the problematic mechanisms of training and certifying them.

“It is no wonder that teacher quality is poor when the tool intended to separate the grain from the chaff is marred with questions that frankly do not make sense,” she said.

To improve the licensure examination for teachers, she urged colleges to submit exam questions for the board of teachers to consider. Then, after the exams, questions should be released in public so proper analysis on validity of questions could be done.

3. Closer collaboration between employers and educators

Links between the two sectors are also important to ensure relevance of curriculum to job-readiness and entrepreneurship. Basillote said these partnerships will increase the pertinence of science and technology research to the economy and the lives of Filipinos.

4. Invest in accountability data

Institutions also need to take international testing to validate if the country is on track when it comes to ensuring the quality of education. Basillote also noted that too few academic programs are accredited for quality.