MARAWI CITY, Philippines — When troops advanced on positions held by Islamist militants in a southern city last week, they were caught in a kill zone.

Technical Sergeant Mahamud Darang said his armored carrier came under fire from a black-clad militant firing rocket-propelled grenades as a column of troops crossed the Agus River toward the commercial center of Marawi City, which militants have held since May 23.

The first grenade hit the ground in front of them, Darang told Reuters. He then spotted the shooter just before he fired again.

“He was on the third floor of a building. Then the second (round) came right into the vehicle and blew up,” said Darang, speaking from a hospital bed, his head and shoulders bandaged from shrapnel wounds.

One soldier died and Darang and some of the others were wounded. Bleeding, the 21-year army veteran ordered his comrades to dismount from the burning vehicle and take cover in a nearby building.

The four soldiers were rescued later and taken to hospital.

The rest of the contingent also came under withering fire from militants in buildings five to ten stories high as they crossed the low-lying Mapandi bridge over the river. Some were hit by Molotov cocktails.

Thirteen soldiers in all were killed and about 40 injured in Friday’s 14-hour battle, a major setback to government forces and a signal that the battle to recapture the city from an estimated 150-200 Islamic State militants will be difficult.

President Rodrigo Duterte has said a couple of times that the battle for Marawi would be over in a few of days.

As Duterte nears the end of his first year in office his strongman image could suffer the longer the fighting drags on. And he could be forced to seek greater support from the United States despite his hostile attitude to Washington since taking power.

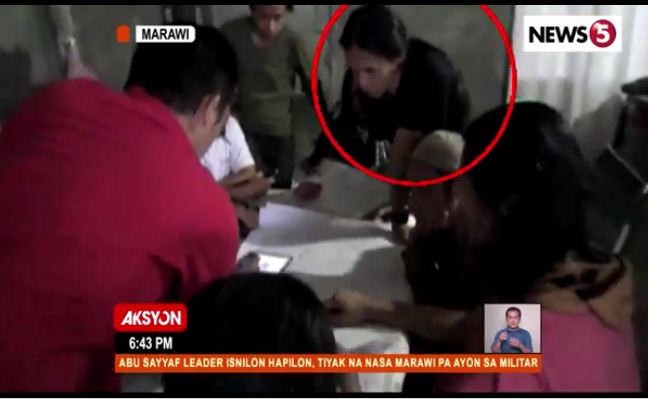

Some U.S. special forces soldiers are providing technical support in Marawi under a long-standing arrangement, and a P3 Orion spy plane and drone aircraft have provided reconnaissance, but U.S. troops are not directly involved in the fighting.

At least eight soldiers on the frontlines in Marawi told Reuters the militants were using accurate sniper fire, grenades and firebombs to hold off advancing troops, despite daily bombing raids and artillery fire on their positions. Many spoke anonymously as they were not authorized to speak to media.

The military says 290 people have been killed, including 58 soldiers, 206 militants and 26 civilians. Residents who have fled the shattered city said they have seen least 100 bodies in the rubble and in battle zones.

The battle for Marawi marks the first time Islamic State has held territory for any length of time in Southeast Asia. Nearby countries like Indonesia and Malaysia, both of which have Muslim majorities, are fearful that it could herald the birth of a regional Islamic caliphate as the militant movement suffers reverses in Iraq and Syria.

Reinforced buildings, high ground

Lieutenant Colonel Jo-Ar Herrera, 1st Infantry Division spokesman, said on Thursday that the army had retaken higher ground to the east of the city, reducing the enemy’s field of fire.

Three bridges over the Agus had earlier been vulnerable to sniper fire, according to a military source, but Herrera said the army now had control of the bridges.

Many of the militants are locals but military officials say they have been joined by battle-hardened Islamic State fighters from as far away as Yemen and Morocco.

The ill-equipped military has mostly operated against rebels in mountainous territory or on remote islands and is unused to urban warfare.

Aiding the militants is Mindanao’s history of clan warfare and most buildings in Marawi have basements and are built with walls of thick concrete.

“The culture of this region is they have built their houses like fortresses,” said one of the frontline army commanders. “They want to protect their families. They know how to make guns. That’s also part of the rido culture.”

The military says its attacks have to be tempered with caution because of civilians trapped in the cross-fire and because it does not want to assault the city’s numerous mosques.

The most fearsome weapon the militants have is a sniper rifle modelled on the U.S.-made .50 caliber Barrett.

“The snipers are good, they make sure that with every shot, someone is killed or wounded,” said Pendaton Guro, a retired colonel who has stayed on in Marawi.

From his rooftop overlooking the city, Guro has watched the fighting since it began on May 23 and heard the popping of sniper fire.

“The Maute leaders were trained abroad. It’s hard to fight them.”

If the army uses armored carriers, the militants respond with rocket-propelled grenades that can penetrate the armor or shower metal splinters within the vehicle.

“Their RPGs make it hard for our armor to advance. If we get too close, they will fire RPGs,” said a soldier who said he had lost four close comrades in the siege.

Troops have responded by rigging wooden panels — adorned with painted images of skulls or slogans — on their armored personnel carriers to repel rockets.

A grenade “will explode as soon as it hits the wood block, and it will not explode on the metal,” a combat policeman told Reuters.

Well-stocked

Although the military has said it has thrown a cordon around the city, the militants appeared to have good stocks of food and ammunition. The assault on Marawi began just before the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, when many Muslim families store food because they do not eat in daylight hours.

“They put ammunition and different arms in different places,” said Marawi City police commander Superintendent Marlon Tabaya.

“I believe they have planned it for a long time.”

The military is using OV-10 planes for regular bombing raids and has pressed tanks into battle, and some units are armed with M-16 assault rifles.

A combat policeman who spent nine days on the frontlines, however, lamented the state of his equipment.

“We have no Kevlar vests, helmets or new weapons,” he said.

Despite the difficulties, troops are confident they will make a breakthrough.

Two front line officers told Reuters radio intercepts indicated that the militants’ ammunition, arms and food supplies were running low.

There were also signs of discord between the different groups fighting in the city, who come from at least three different Muslim-majority ethnic groups.

“They are calling each other, looking for help, thinking they have left each other,” an army radio officer said. “They are demoralized.”

Lieutenant Colonel Herrera said the military was advancing toward the inner city, but added: “There are still sniper positions. We continue to assess the battlefield. The battlefield is very fluid.”

Darang, the wounded armored carrier commander, said he was eager to return to battle.

“When I recover I will go back there to fight,” he said.

A Muslim himself from Cotabato City, the 47-year-old soldier was filled with disdain for the militants.

“They are not good Muslims. How could they attack us during Ramadan, these people have no religion.”