This is part of a series of stories on some — in truth, but a handful — of the families left behind by the thousands of victims of the extrajudicial killings that have marked the war on drugs waged by the government, which also turned one year old with the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte.

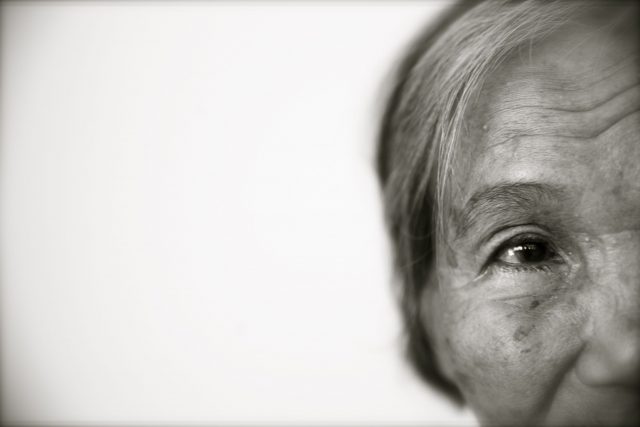

Grazia* is almost skin and bones. Her hair has gone gray, her eyes are watery, and her cheeks are dotted with age spots.

Every day, she works at a junk shop in Brgy. Payatas, Quezon City, where she segregates trash to look for recyclables that can earn her some money.

At 84 years old, she is twelve years older than President Rodrigo Duterte. Other senior citizens may have retired at this point, she cannot afford to.

Grazia’s son Henry* was 38 when he was killed in December. Her daughter-in-law Hilda* is detained at the Quezon City Police District headquarters in Camp Karingal, supposedly for being a “big” drug pusher.

So Grazia takes care of her seven grandchildren, including an eight-month-old infant, by herself.

She remembers cooking at home when she heard a bang from downstairs.

“Siguro may tinokhang na naman (Maybe someone was killed again),” she recalls thinking at the time, and manages a laugh. “‘Siguro meron na namang hinabol sa baba,’ sabi ko pang ganyan, kasi nasanay na akong patay dito, patay doon (‘Maybe they were chasing after someone there,’ I even said, since I’d gotten used to killings here and there).”

It is telling how the seemingly innocuous tokhang (from the Bisaya words toktok, or knock, and hangyo, or plead), the police’s door-to-door campaign the government claims has convinced more than a million drug pushers and users to surrender, is also associated with the thousands of deaths — both in what authorities maintain are “legitimate” anti-narcotics operations and the vigilante-style executions and street shootings by unknown killers — that have marked the government’s war on drugs.

When Grazia went down to see what the commotion was, one of her grandchildren told her: “May mga pulis, Lola, sa bahay natin (Grandma, there are policemen in our house).”

That was when she saw the men dressed in black — she remembered one was fat — hovering over her kneeling son. Two of the men grabbed her to keep her from coming closer.

Grazia heard Henry say, “Maawa na po kayo, sir (Have mercy, sir).”

She joined her voice to his, saying, “Imbestigahan niyo na lang ‘yung anak ko. Maawa naman kayo, sir (Just investigate my son. Have mercy, sir),” over and over again.

The reply of the men who held her back: “Hindi naman namin papatayin kung hindi lumaban (We won’t kill him if he doesn’t fight back).”

“Sir, hindi lalaban ‘yung anak ko (my son won’t fight back),” Grazia promised.

She struggled to free herself from their grip, deliberately falling on her back to loosen their hold, and rolled on the floor to buy time.

But the next thing she knew, her son was sprawled on the ground, blood spouting from his chest and forehead. Grazia didn’t see how Henry was killed because of the men holding her back. But she heard the shots.

“Nu’ng pumutok, humiyaw talaga ako (When the shots rang out, I really screamed),” she recalls.

She begged them to bring him to the hospital. “Mabubuhay pa ‘yan, sir (He can still be revived, sir)!”

Henry had worked for the dump trucks that made their way to Payatas with their loads of Metro Manila’s trash.

Grazia says she was told he was on the drug watchlist, although she insists that only the friends he hung out with were involved with the illegal stuff. She heard that he supposedly sold shabu and “marked money” had even been found on his person.

She denies everything, especially the label “nanlaban” (fought back).

“Paano magkaroon ng baril? Kaya ‘pag nababalitaan ko na ganyan, hindi ako naniniwala talaga kasi saksi po ako sa pagkamatay ng anak ko na wala kaming baril sa bahay na ‘yun. Hindi talaga lumaban ang anak ko (Where would he get a gun? That’s why when I hear news reports like that, I don’t believe them. Because I was a witness to my son’s death, and I know there was no gun in our house),” Grazia says.

The feeling that her son had done nothing to deserve his fate gives her fervor despite her feebleness.

“Sana naman po, kagalang-galang na Pangulo … piliin niyo naman ‘yung totoo. Hindi naman ako tumututol sa batas na binigay mo, dahil pasalamat nga kami para talagang matahimik na ‘yung ano natin dahil wala nang mga adik. Pero naman po, paimbestigahan niyo muna (Please, honorable President, choose the ones who have been proven guilty. I am not against the law you laid out, because I’m even thankful that our society will become more peaceful without the addicts. But please, investigate first),” Grazia says.

“Dahil sabi niyo naman ‘yung mga adik ipapagamot niyo, ‘di ba? Bakit ‘yung anak ko, hindi naman adik, nagmamakaawa sa mga pumatay sa kanya, bakit mo hindi naman pinagbigyan?Pakisabi niyo naman sa pumapatay, na sana imbestigahan naman nila ‘yung mga hindi adik. Pinagapapatay po nila (Didn’t you say that you would have addicts treated? What about my son, who wasn’t even an addict and had pleaded for his life? Why didn’t you give him a chance? Please tell the people who kill to please investigate to find out which ones aren’t addicts. Because they just killed them all),” she adds.

A mere accusation from a neighbor should not be the basis for murdering a person, Grazia insists. Yes, she wants peace, but not at the cost of innocent lives.

“Pito ‘yung apo ko. Pito ‘yung anak ng anak ko na walang bumuhay na, (I have seven grandchildren. My son has seven children who no longer have anyone to support them),” she says. “Maawa ka naman, kagalang-galang na Pangulo. Maawa ka. Intindihin mo naman ‘yung mga anak ng mga tao na hindi adik. Hindi lahat adik (Have mercy, honorable President. Have mercy. Please think about the children of the people who aren’t addicts. Not everyone is an addict).”

*Names have been changed to protect the people’s identity.