This story was produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, Department of Transportation and VERA Files.

When a group of architects grew weary of dealing with Metro Manila’s traffic, they brainstormed a solution that, on hindsight, seems obvious.

“Let’s build an elevated walkway and bikeway along EDSA and leave our troubles below. Since EDSA cannot be fixed, and we cannot share the road because of all the traffic schemes, it would be impossible to build bike lanes along EDSA,” architect and urban planner Dan Lichauco, who also serves as the group’s leader, says.

The group initially tried to collect 50,000 signatures through an online petition calling for government action against traffic congestion, pollution and commuting stress on EDSA.

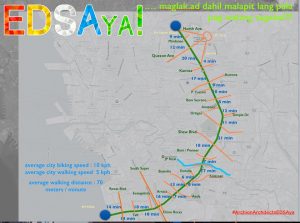

The petition is based on “EDSAya! by Built Environment Banter,” the “uncommissioned and self-funded study” of Archion Architects, a firm headed by Lichauco, to build a 19.5-kilometer elevated walkway and bikeway from the Mall of Asia Complex in Pasay City to North Avenue in EDSA.

The aim is to connect the various central business districts along EDSA, such as Makati, Taguig, Mandaluyong, Ortigas and Cubao, to give commuters the option to walk or use their bikes to and from work instead of taking a car, bus or the MRT.

Lichauco says that advocates have forwarded the study to government officials while he is currently in exploratory talks with agencies, including the Metro Manila Development Authority.

If the study becomes reality, it would be a huge boost to bicycle riders like Junlee de Luna, a contractual janitor who uses his bike to travel from his home in Pook Ricarte, Diliman to the Sampaguita dormitory at the University of the Philippines where he works.

He cycles to run errands and, at times, uses his bike to take his daughter to school. Overall, he saves as much as P3,000 each month on fares, an amount that helps augment the family’s budget for food and schooling expenses.

The average Filipino family spends 20 percent of monthly income on transportation, according to a study published in 2014 by the Japan International Cooperation Agency. Cycling reduces transportation costs, particularly for those in the lower income brackets.

Aside from the savings, an elevated bikeway could be a boon to those who face the daily risk of getting run down on the metropolis’ busiest thoroughfare.

Elevated bikeways have become a trend among urban planners, both as a way to protect cyclists and create new spaces in highly congested cities.

Copenhagen — one of the most cyclist-friendly cities in the world — erected the Cykelslangen or “Cycle Snake” in 2014. The cycling skyway, designed by architectural firm DISSING + WIETLING, connects the city’s harbor bridge to the highway, eliminating the hassle of bringing bikes up and down steep stairs and sharing narrow spaces with pedestrians.

By allocating separate pathways for cyclists and for pedestrians, mobility and safety for both are enhanced. Not surprisingly, the infrastructure has been well-received by Copenhagen residents and urban planners all over the world.

Studies show that bike lanes in cities such as Amsterdam and Copenhagen have succeeded in reducing cyclist deaths and improving accessibility.

The vastly diminished space on EDSA leaves little doubt that cyclists, motorists and pedestrians sharing the highway is no longer feasible.

The dominance of four-wheeled vehicles in the country puts vulnerable road users, such as motorcyclists and cyclists, at a disadvantage, says Dr. Ricardo Sigua, a professor at UP’s Institute of Civil Engineering and research fellow at the National Center for Transportation Studies, also at UP.

Data collected by the Metro Manila Accident Recording and Analysis System shows fatal road crashes in Metro Manila on the rise. In 2016, 299 crashes were recorded daily, up from 262 in 2015.

The World Health Organization says bicyclists, motorcycle riders and pedestrians suffer disproportionately in the event of collisions with four-wheeled vehicles as they are not protected by a shell.

Despite the risks, cycling, long popular with health buffs, is fast gaining popularity among commuters trying to save on fare money. It also allows them to avoid long commutes due to the heavy traffic on Metro Manila’s roads, which also bleeds the economy badly — P2.4 billion daily, according to JICA, an amount that could rise to P6 billion by 2030.

Metro Manilans’ quality of life has also deteriorated due to traffic, with a survey by the navigation app Waze showing a resident spends an average of 45.5 minutes commuting from home to office, although daily hours-long gridlocks are increasingly becoming commonplace.

Pollution from heavy traffic also contributes to respiratory and cardiovascular ailments of Metro Manila residents, says a study conducted by the NGO Kaibigan ng Kaunlaran ng Kalikasan, which found that 76 percent of air pollutants in the city came from vehicular emission.

“The whole idea of trying to fix EDSA with better and more trains (and other transport solutions) boils down to making it more accessible to pedestrians and bikers,” Lichauco says.

He adds that too much infrastructure on EDSA — overpasses and bridges, for example, that were not built according to the National Building Code — make cosmetic changes along the highway no longer feasible.

Some of the overpasses along EDSA are unnecessarily high, Lichauco says.

The Building Code mandates that a step must have a 23-centimeter rise and a 30-cm width. However, Lichauco and his team found that most overpasses have steps that do not meet these requirements, producing 20 more unnecessary steps and making climbing more difficult, especially for PWDs and the elderly.

In Lichauco’s plan, the elevated walkway will be designed according to the National Building Code, while also adding greenery and protecting the space from pollution. More crossing points between various destinations along EDSA will likewise be added to make walking between short distances easier.

At the moment, EDSA has a total of 45 crossing points, he says. In the plan, he intends to add 25 more to make travelling on foot or by bike more convenient.

Pollution, narrow sidewalks and erratic weather also push many Metro Manila commuters to take street-level transportation to distances they could otherwise reach on foot. Lichauco hopes to change this, believing commuters would choose to walk short distances if proper walkways and protection from the elements were available.

Once this happens, it would help lessen gridlocks and the onerously crowded mass transit systems. The MRT, for example, has been operating beyond its capacity since 2004, ferrying some 500,000 people daily, or 142 percent more than its 350,000-passenger capacity.

Cyclist groups and urban planners have long clamored for the roads of Metro Manila to be more pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly. Aside from reducing road crashes, if more residents could be enticed to walk and cycle to short-distance destinations, there would be less cars on the road.

But while the government has included plans for cyclists and pedestrians in its Philippine Road Safety Action Plan — a comprehensive, multi-agency transportation plan led by the Department of Transportation — new infrastructure dedicated to pathways protecting vulnerable road users is conspicuously absent in the 2017 Infrastructure Program of the Department of Public Works and Highways, which earmarks P247 billion for the construction of new highways and toll ways to increase vehicle usage capacity in the country. This includes the budget for the construction of the NAIA Expressway, the Cavite-Laguna Expressway and the NLEX-SLEX connector.

Local efforts by various agencies are underway, according to government officials. MMDA General Manager Julia Nebrija has said that plans for the C6 — a 34-kilometer toll road from Taguig to the Batasan Complex in Quezon City — will integrate a bikeway and that more plans to improve roads for pedestrians and cyclists are underway.

But the government has not announced any plans for the construction of walkways and bikeways on major thoroughfares such as EDSA, a project that could benefit thousands of working-class commuters.

Prof. Sigua explains that building an elevated facility would be expensive. He instead suggests the improvement of sidewalks and the proper implementation of the Building Code.

But In Lichauco’s EDSAya, he estimates that erecting an elevated walkway could cost P6 billion and be faster than building a subway system.

“I think it can be built in two years but it can also be built in segments,” he says.

While there have been several bills filed in Congress to promote biking as an alternative mode of transportation, none have become law. Most bills also relegate the implementation of bike promotion projects to local government units, which could prove problematic in the case of EDSA, which is shared by different cities.

In the meantime, De Luna says he would like to ride his bicycle to the Fairview Public Market, where his family shops for food, but fears that it might be too dangerous to cycle along Commonwealth Avenue.

“Mahirap ‘pag bisikleta. Pag nabangga ka doon, sigurado durog ka (It’s difficult to ride a bike there. If you are involved in a crash, you’re sure to be crushed),” he says.