PORTLAND, Oregon — On July 20, a Hong Kong-flagged cargo ship departed Charleston, South Carolina carrying thousands of containers. One of them held a lucrative commodity: body parts from dozens of dead Americans.

According to the manifest, the shipment bound for Europe included about 6,000 pounds of human remains valued at $67,204. To keep the merchandise from spoiling, the container’s temperature was set to 5 degrees Fahrenheit.

The body parts came from a Portland business called MedCure Inc. A so-called body broker, MedCure profits by dissecting the bodies of altruistic donors and sending the parts to medical training and research companies.

MedCure sells or leases about 10,000 body parts from U.S. donors annually, shipping about 20 percent of them overseas, internal corporate and manifest records show. In addition to bulk cargo shipments to the Netherlands, where MedCure operates a distribution hub, the Oregon company has exported body parts to at least 22 other countries by plane or truck, the records show.

Among the parts: a pelvis and legs to a university in Malaysia; feet to medical device companies in Brazil and Turkey; and heads to hospitals in Slovenia and the United Arab Emirates.

Demand for body parts from America — torsos, knees and heads — is high in countries where religious traditions or laws prohibit the dissection of the dead. Unlike many developed nations, the United States largely does not regulate the sale of donated body parts, allowing entrepreneurs such as MedCure to expand exports rapidly during the last decade.

No other nation has an industry that can provide as convenient and reliable a supply of body parts.

Since 2008, Reuters found, U.S. body brokers have exported parts to at least 45 countries, including Italy, Israel, Mexico, China, Venezuela and Saudi Arabia. Whole bodies are studied at Caribbean-based medical schools. Plastic surgeons in Germany use heads from dead Americans to practice new techniques. Thousands of parts are shipped overseas annually; a precise number cannot be calculated because no agency tracks industry exports.

Most donor consent forms, including those from MedCure, authorize brokers to dissect bodies and ship parts internationally. Even so, some relatives of the dead said they did not realize that the remains of a loved one might be dismembered and sent to the far reaches of the globe.

“There are people who wouldn’t necessarily mind where the specimens were sent if they were fully informed,” said Brandi Schmitt, who directs the University of California system’s anatomical donation program. “But clearly there are plenty of donors that do mind and that don’t feel like they’re getting enough information.”

MedCure shipments are now the subject of a federal investigation. In November, the Federal Bureau of Investigation raided the company’s Portland headquarters. Though the search warrant remains sealed, people familiar with the matter say it relates in part to overseas shipping.

MedCure is cooperating with the investigation, said its lawyer, Jeffrey Edelson. He declined to comment on the FBI raid, but said: “MedCure is committed to meeting and exceeding the highest standards in the industry. It takes very seriously its obligation to not only deliver safe specimens securely, but to do it in a way that respects the donors.”

Edelson also said MedCure “partners with government and industry agencies to follow and exceed requirements for shipping human tissue,” and that “shipping handlers, drivers and carriers are specially trained for the safe handling and transportation of human specimens.”

Infected parts at the border

As a Reuters series last year revealed, the body donation industry is so lightly regulated in the United States that almost anyone can legally buy, sell or lease body parts.

Although no federal law expressly regulates the body trade, there is one situation in which the U.S. government does exercise oversight: when body parts leave or enter the country. Border agents have the authority to ensure that the parts are not infected with contagious diseases and are properly shipped.

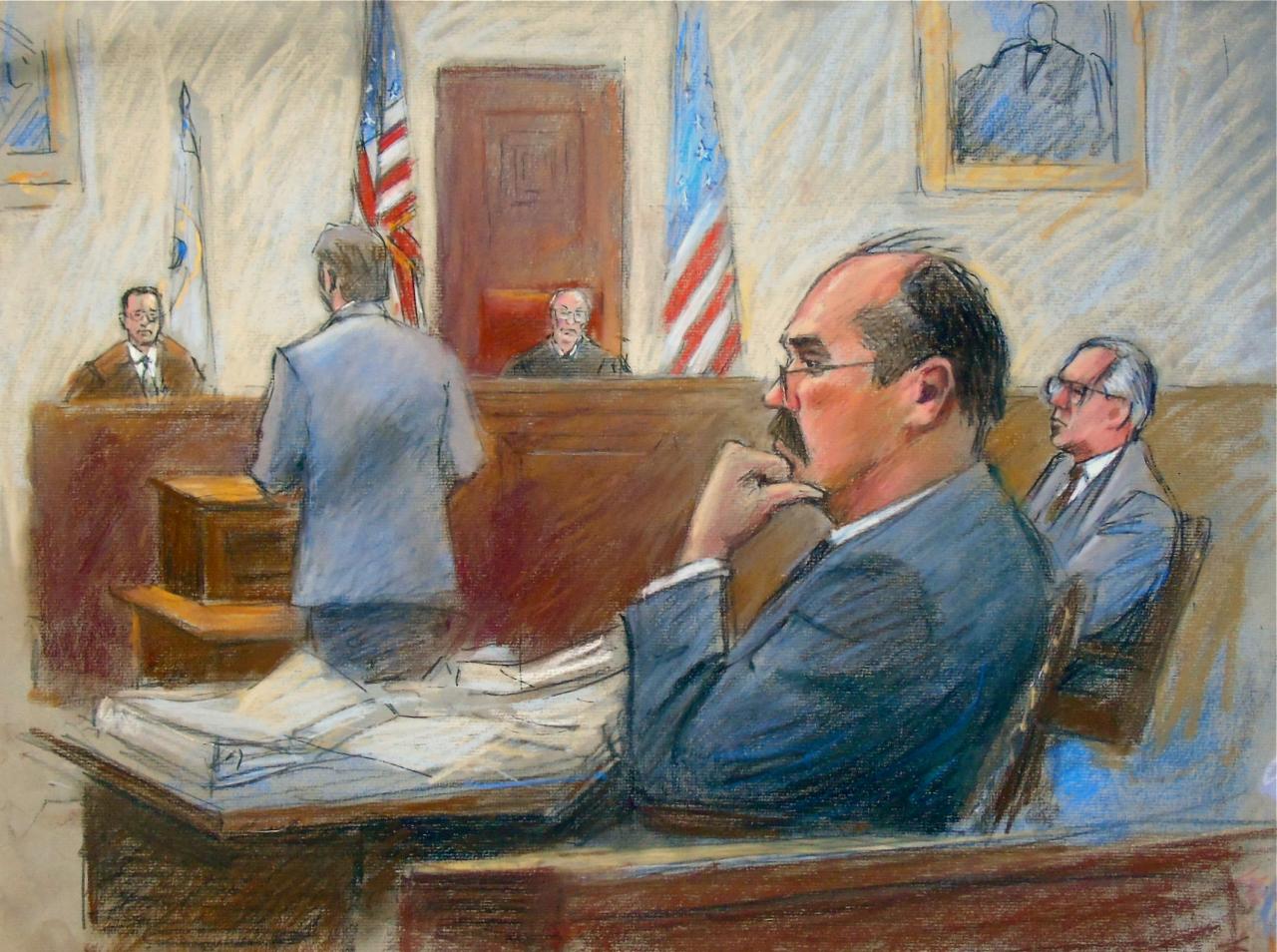

This authority played a leading role in the government securing a conviction last month of Detroit broker Arthur Rathburn, who stored body parts in grisly, unsanitary conditions, according to trial testimony. The FBI began to focus intently on Rathburn’s business, International Biological Inc, after repeated border stops in which he was found ferrying human heads, court records show.

The jury found that Rathburn defrauded customers by supplying body parts infected with HIV and hepatitis.

“The fraud scheme orchestrated by IBI shocked even the most experienced of our investigative team,” said FBI special-agent-in-charge David Gelios. Even in death, Gelios said in a statement after the verdict, donors were “victimized as IBI intentionally and recklessly marketed and transported contaminated human remains… Personal greed overcame decency.”

Rathburn was also convicted of transporting hazardous materials — the head of someone who had died of bacterial sepsis and aspiration pneumonia. The transportation conviction underscored the U.S. government’s growing concern about shipments of body parts that might endanger public health, officials said.

Martin Cetron, director of Global Migration and Quarantine for the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, said that when brokers dissect a body that is infected, there is added risk of transferring that disease to anyone who handles the parts.

“In the case of saws (used) to cut bones or limbs, there may be additional procedures that could potentially turn a fluid into an aerosol that could be inhaled and be communicable,” Cetron said.

A Reuters review of government records shows that border agents intercepted body parts suspected to be infected at least 75 times between 2008 and 2017. Border agents pay more attention to goods entering the country than those departing, and virtually all of the intercepted shipments were remains of American donors whose body parts were being returned to United States. Typically, body parts are returned to America for three reasons: to comply with foreign laws on final disposition; when cremation is not available in the foreign country; or when a U.S. broker intends to reuse the parts.

In 2016 and 2017, for example, federal agents stopped shipments being returned to MedCure at the border, law enforcement records show. The body parts they stopped included torsos carrying infectious biological agents that cause sepsis, a body’s extreme response to infection. At least one carried the life-threatening MRSA bacteria, the records show.

For more than a year, records show, U.S. officials and some body brokers have disagreed over whether the presence of sepsis in a corpse — without further information about a person’s cause of death — poses enough of a risk to warrant special packaging and warning labels.

“Sepsis itself is not a disease diagnosis but it raises a red flag,” said Cetron, the CDC official. The pathogen that caused sepsis, he said, “could be a bacteria, could be Ebola, could be salmonella, could be E. coli.” That’s why further documentation, including a death certificate, must accompany any body part imported into the United States, he said.

The CDC has an exemption intended to allow for shipping blood and other lab testing samples. Reuters found dozens of examples of brokers labeling customs manifests and packages with a version of the term “exempt human specimen” to ship body parts.

“I think that’s a deceptive practice,” Cetron said. “If they are human remains, part or in whole — heads, arms, limbs, etc. — they are not exempted.”

Several brokers said the government should clarify the rules — whether the CDC’s or those of other regulatory entities. They cited, for example, a U.S. Department of Transportation regulation that, they believe, exempts body parts. Transportation officials declined to comment on their regulations.

Alyssa Harrison, executive director of Oklahoma-based broker United Tissue Network, said most in her industry want to follow the law. But, she added, “there are many guidelines that are unclear and or contradictory to other department’s regulations.”

The disconnect between what the industry and government believe is dangerous, and what precautions are required by law, should be resolved, said Matthew Zahn, chairman of the public health committee for the Infectious Diseases Society of America, a group that represents doctors, researchers and other health professionals.

“It’s a situation where we don’t have a huge amount of regulation or clarity as to what the risks are,” Zahn said. “It feels like one of those cracks in the system where a practice has developed and the risk factors and oversight have not fully matured.”

Exporting Americans

MedCure, founded in 2005, describes itself, as do most body brokers, as a non-transplant tissue bank. It has distribution hubs and surgical training centers near Portland, Oregon; Las Vegas; and Providence, Rhode Island. The company also has distribution hubs near Orlando and St Louis.

When MedCure donors die, the cadavers are transported to one of these five U.S. hubs. According to former employees, MedCure deploys a temperature-controlled truck to carry body parts between the five facilities.

MedCure began shipping cadavers and body parts overseas as individual orders, one by one, and largely by airplane. The former employees said the company later calculated that it could increase profits by shipping bulk quantities of body parts to Europe, and distributing them from there.

In 2012, MedCure opened its European hub in Amsterdam. Since then, MedCure has sent to the Netherlands at least six refrigerated cargo containers filled with frozen human remains, manifest records show. The first container — 40 feet long, 8 feet wide, 9.5 feet tall — departed the Port of Tacoma in Washington state in July 2012. The body parts weighed about 5,000 pounds (2,268 kg) and were valued at $259,210.

MedCure continued to export via truck and plane as well — for example, shoulders to a hospital in Mexico, knees to a surgical training center in Taiwan and a head to a university in Chile.

The shipments are detailed in internal MedCure documents and in data from two companies that collect trade manifests: Descartes Datamyne of Ontario, Canada, and PIERS, a unit of IHS Markit Maritime & Trade, based in London.

One reason foreign doctors and researchers rely on U.S. companies for body parts: Their nations restrict the dissection, sale and distribution of donated cadavers.

In many nations, certain sects of religions – from Judaism to Islam to Taoism — frown upon separating the bodies of the dead into parts. Huang Yi-Ling, who worked in Singapore for a medical device manufacturer, said that importing body parts from the United States avoids “conflict with donor intent” in regard to religion.

“MedCure makes donor tissue available for researchers and teaching facilities even in places where religious and cultural norms discourage body donation,” said Edelson, the MedCure lawyer.

Holger Gassner, director of the Finesse Center for Facial Plastic Surgery in Regensburg, Germany, said he began importing body parts from the United States in 2009 because he couldn’t obtain the volume of heads he needed locally for medical conferences. He also said most German anatomy departments use formalin to preserve bodies; MedCure supplies fresh body parts, which are more useful for teaching.

“You have to practice on human tissue in order to become a good or better surgeon,” Gassner said. “There’s no alternative.”

Gassner described MedCure as “very reputable” and noted that it sent an inspector to Germany to approve his facilities. “At the end of the day,” he said, “this has been a very positive thing for us and for the university.”

‘Serious worry’

The FBI search of MedCure in November is part of a national investigation by the bureau of body brokers, many of whom did business with each other.

MedCure, for example, was among the brokers who supplied Rathburn, the Detroit businessman convicted last month. MedCure was not accused of supplying any body parts at issue in the Rathburn trial.

A different Rathburn supplier, Steve Gore of Phoenix, pleaded guilty to providing customers with infected body parts. A Reuters report in December described how Gore’s business used construction saws to dismember donated bodies and employed an untrained intern to rip out cadavers’ fingernails with pliers.

In early 2016, authorities stopped nine torsos that were being returned from Vancouver, Canada, to MedCure in the United States. According to U.S. government records reviewed by Reuters, some torsos were infected with sepsis. At least one had MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Border officials in both countries struggled to verify the identities of the torsos and how they were used. The records show that officials determined that a Vancouver-area bioskills seminar to which the torsos were purportedly sent did not exist.

Canadian and U.S. officials said they do not comment on specific cases. Edelson, the MedCure lawyer, said the government’s account is inaccurate and “the training course was a legitimate medical program.” He said the company does not sell or rent out human remains infected with HIV or hepatitis, and that body parts with other “non-contagious conditions are shipped overseas only with the permission of the CDC, including CDC permit, proper labeling and packaging and full disclosure” to its foreign clients.

In January 2017, another shipment being returned to MedCure from Hong Kong was stopped at the U.S. border. This one contained six torsos with legs. MedCure had sent the body parts to the Orthopedic Learning Center at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, which trains surgeons.

The specimens were used to test the biomechanics of a knee implant procedure, including the impact of the technique on muscles connecting to the pelvis and femur, said the center’s director, Jack Chun Yiu Cheng. The doctor would not disclose which company or individual had organized the workshop.

Reuters reviewed a copy of the MedCure medical summary accompanying the specimens noting that two of them carried sepsis, including one from a donor who died in part from “septic shock.” When asked about the summaries, Cheng said there was not enough information provided to determine what caused the septic shock, but he said that he would not have used the body parts himself.

“I would have serious worry,” Cheng said.

Any training workshop carries risk, he said. But going forward, the doctor said, the training center will probably reject torsos with sepsis, “or at least discuss it directly with the workshop leader, not just send them the forms.”

Edelson, the MedCure lawyer, said the company discloses appropriate medical information. He added, “Recipients are medical professionals who are expected to use basic safety precautions when handling any human tissue, including wearing gloves, masks and scrub suits.”

Reading the fine print

Some donor relatives said they were disappointed to learn their loved one’s parts were sent overseas.

“I should have read the fine print,” said Marie Gallegos, whose husband’s head was shipped to a dental school in Israel months after he died of a heart attack in May 2017.

Six hours after he died, she said, an employee from Donate Network of Arizona called to discuss body donation. The employee promised the body would advance medical research and be treated with dignity, Gallegos said.

She recalled signing two consent forms, one for Donate Network and one for the company she was told would handle the cremation, United Tissue Network. The UTN form authorized use of her husband’s body parts “both domestically and internationally.”

Later that summer, UTN delivered her husband’s ashes, which she buried at a veterans’ gravesite. She said she did not realize the ashes represented only a portion of her husband’s remains. UTN still had his head and in the fall shipped it to the Tel Aviv dental school.

“Had I known that my husband’s head was over there, I would have waited to have the ceremony,” she said. “If they really wanted my husband’s body for these purposes, they should have told me upfront and verbally.”

Donor Network declined to comment about this case. UTN executive director Alyssa Harrison said, “We make it very clear for families to understand our whole process before deciding to donate.”

Heads in limbo

If not for the keen eye of a Phoenix airport worker, Marie Gallegos might not have learned what became of her husband’s remains.

On November 1, as Daniel Gallegos’ head and the heads of six other donors were returning from Israel to UTN in Arizona for cremation, someone noticed a discrepancy on the shipping documents. According to records reviewed by Reuters, the shipping manifest described the contents as “electronics” valued at $10 each. A label on the coffin-sized package described the contents as human remains.

Government records show that border officials were troubled that the package appeared punctured and a strong smell was wafting from the box. They also demanded death certificates to ensure that the specimens were disease-free, records show. One of the donors, records show, carried staphylococcus aureus, an infection the CDC website says poses a potentially serious risk to healthcare workers.

After officials stopped the package in Arizona, documents reviewed by Reuters show, UTN employees disagreed with border authorities about whether the package was damaged or death certificates were required. It took three weeks to resolve the dispute, according to the documents. The government then released the heads and they were cremated.

UTN’s Harrison told Reuters the electronics designation was “human error” and the package was sent in a leak-proof container. She disputed the government’s contention that further documentation should have accompanied the shipment, arguing that “a diagnosis of sepsis in the clinical setting does not confer any specific risk.”

Harrison said UTN and the freight company followed all laws and regulations covering the export and import of human medical specimens.

“The CDC should not have gotten involved,” she said.

Milli Raviv, whose Tel Aviv-based International Dental Studies center leased the heads from UTN, said her school maintains “high standards” to protect students.

On shipping documents, Raviv was listed as the contact person in Israel for shipping the heads back to UTN’s Phoenix office. Even so, the dentist professed ignorance about why the package was mislabeled.

“No idea about shipping,” she said.