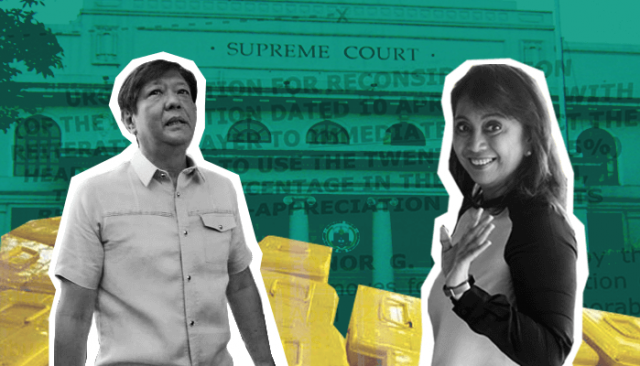

Any major electoral recount is bound to be messy, and the revisiting of the 2016 race between Vice President Leni Robredo and her defeated opponent Bongbong Marcos exemplifies an unfortunate consequence of democracy.

The public gaze on the judiciary in recent weeks ping pongs from the Sereno impeachment proceedings to the vice presidential recount. Much of what the Supreme Court has done while sitting as the Presidential Electoral Tribunal then has been subject to intense scrutiny.

The PET recently decided to invalidate at least 5,000 ballots for being shaded less than 50 percent of the oval next to the candidate’s name on the ballot. Supporters of Robredo, in response, called for a protest to accompany her motion for reconsideration.

LOOK: Vice President VP Leni Robredo files appeal before the Presidential Electoral Tribunal (PET) to bring back vote threshold to 25%. | via Edd Gumban pic.twitter.com/iCGFXyNCCI

— The Philippine Star (@PhilippineStar) April 19, 2018

Presidential Electoral Tribunal changes the basis for the vote recount! Mananakaw ang mga boto natin! LENI is our duly elected VP! Assemble tom (april 19) 8:00 AM sa labas ng Lapu-Lapu Monument sa may Rizal Park. We will march to the Supreme Court!#LabanNiLeniLabanKo!!!

— Ma. Socorro Naguit (@harbingerof1) April 18, 2018

Adding to the controversy was a document posted by Pinoy Ako Blog, which supports Robredo and the Liberal Party, apparently suggesting that the PET earlier consented to partial shading of at least 25 percent of the provided oval on the ballots.

Former Comelec chair and election law expert Sixto Brilliantes Jr. took Robredo’s side, questioning why the PET used the 50-percent threshold when a 25-percent threshold was considered in the manual audit of the presidential race of the 2016 elections.

Meanwhile, several Marcos supporters are decrying the PET’s decision to stall the recount and prolong its decision.

The PET and its powers

The PET was not originally a product of an express constitutional decree unlike its counterparts in the House of Representatives and the Senate, but of special law.

On June 21, 1957, Republic Act 1793 was passed creating the Presidential Electoral Tribunal to be “the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns, and qualifications of the president-elect and the vice-president-elect of the Philippines.”

The Supreme Court en banc was to preside as the PET, with the chief justice at its chairman.

The current 1987 Constitution finally came, explicitly stating the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction.

The validity of the PET was first challenged by former Vice President Fernando Lopez in the landmark case of Lopez v. Roxas, questioning its authority to review losing candidate Gerardo Roxas’ poll protest.

In upholding RA 1793, the court found that the SC sitting as the PET did not constitute a separate court from the highest tribunal. The powers of the PET were also deemed part of the power of judicial review enshrined in the Constitution and could therefore review electoral contests.

The current 1987 Constitution finally came, explicitly stating the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction.

“The Supreme Court, sitting en banc, shall be the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns, and qualifications of the President or Vice-President, and may promulgate its rules for the purpose,” states Section 4, Article VII for the Constitution.

In other words, it is solely the high court that has the final say when it comes to presidential and vice-presidential electoral protests.

Interestingly, Macalintal, Robredo’s counsel, was the defeated petitioner in the 2010 case of Macalintal v. PET. There, Macalintal questioned the validity of the court to sit as the PET anew.

The high court affirmed its own power to sit as the PET, but held that Macalintal had previously recognized the tribunal’s jurisdiction as he had already appeared before it in the 2004 elections.